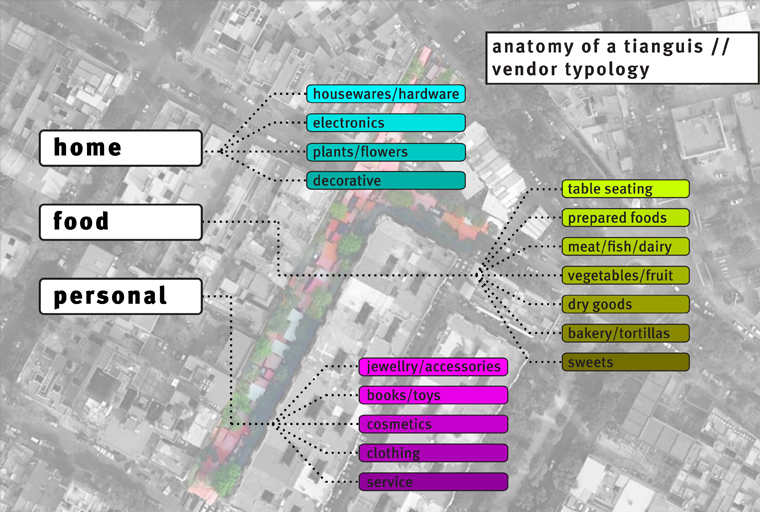

Vendors, mercados and tianguis have been at the core of my investigations here in Mexico City; the Tuesday tianguis on Pachuca Street near my house is both the first one found, and the one to which I have returned most frequently. As a brief interlude in the theorizing, I thought it would be fun to look at this un-exceptional example in a bit more depth, so last week I set out to map my local market (much to the confusion of the vendors hawking their wares in my direction).

I conceived of this exercise without any particular outcome in mind – rather, I simply wanted to quantify and analyze what had so far been a qualitative and experiential understanding of a place.

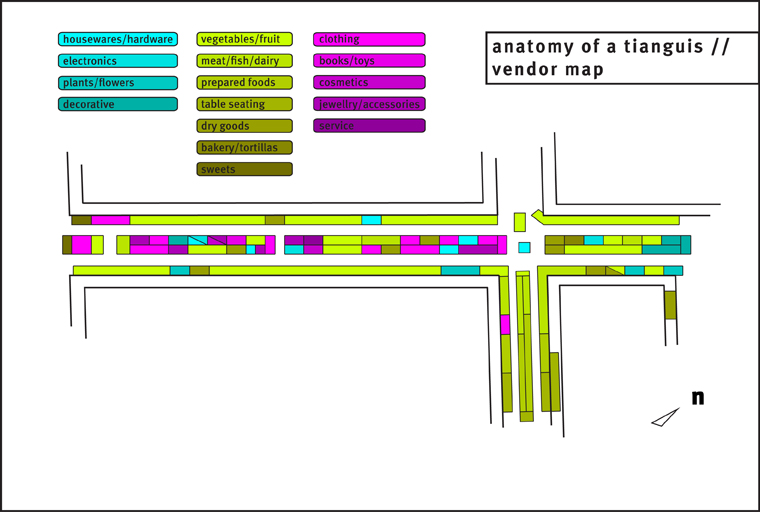

What I found speaks clearly to the demographics of the tianguis: the prepared foods are clustered on the south-eastern spur of the main strip, allowing for easy entry and exit for the lunch crowd, many of whom do not actually enter the rest of the market, having come only to eat. In the main two-block stretch of the tianguis, the map reflects a clear distribution of products by category, with all but two of the consumer goods vendors located on the inside of the two main aisles, mostly concentrated in the western section.

The produce occupies the most privileged real estate, running along the outside edge of both of the market’s main aisles; it is also by far the most prevalent category of product on offer. Not reflected by the map is the fact that the produce is also loosely sorted by type – fruit vendors in one stretch, vegetable sellers in another, etc. Readers who frequent US farmers’ markets will find this familiar – in many senses a normative tianguis is a sort of farmers-market-plus.

On the whole, the market seems targeted at familial and household needs, with the few exceptions offering personal consumer items for women and children. This is backed up by my observations to the effect that the bulk of the shoppers are women, seemingly a mix of homemakers and household staff.

The officially sanctioned tianguis in Mexico City, clearly identifiable by their pink booths and tarpaulins as well as the government signage draped everywhere, are well organized and relatively transparent. Vendors pay a daily fee (in the range of 100 pesos) for the right to sell their wares. Most of them sell at more than one tianguis per week – by some counts there are as many as 1,400 tianguis in Mexico City alone.

As much as I have come to love tianguis, however, I have begun to think that they offer as many counter-examples for my work as they do inspirations. They rely on capital to drive their re-appropriation of urban space, which is highly tactical on an economic (and perhaps social) level, but evinces few spatial ramifications. That is, they are so thoroughly assimilated into the city’s consciousness that people have ceased to register their presence as in any way transgressive.

Perhaps a fairer interpretation would be that the tianguis represent a sort of end-stage in the trajectory of the temporary in the city – so successful and accepted that they have become one more piece of the formal apparatus of urban governance. A laudable goal, and one which clearly increases the performance and utility of the street, but which offers scant clues to the beginning/pupal/experimental phase of temporary uses on which I have focused my gaze.