A few weeks before I left Tokyo, I was fortunate enough to have the chance to spend some time speaking with Kengo Kuma. In addition to being (in my totally unbiased opinion) one of the most consistent hit-makers in the architectural firmament, Kuma-san also indirectly kick-started this research when I saw his Casa Umbrella project in a book.

As you can imagine, my expectations were high; happily, Kuma-san's answers to my questions proved as thoughtful as his structures themselves.

nj :: So, some of the inspirations for my research are your installations, like the Casa Umbrella and some of the teahouses you’ve done in the last couple of years – the temporary structures.

I’m interested to hear your thoughts on installations: why you make them, if you enjoy them, and we can just kind of go from there.

kk :: Hmmm… Yeah. Can I start with the Casa Umbrella project?

Sure.

So that project was for an exhibition, titled “Casa de Tutti”, “The House for Everybody”. And I’m very much interested in the democracy of architecture; democracy means that the daily life and the construction of the building are integrated. In the case of Casa Umbrella, the umbrella is basically for daily use, but…

If one can have this special umbrella in front of the house – if an earthquake happens, you can bring the umbrella without anything else. And if fifteen people can come together with fifteen umbrellas, they can build the house by themselves, in a few hours. That is the system of Casa Umbrella – the umbrella is part of daily life, and also it is part of the disaster kit. So one special umbrella can belong to two different contexts: that is my idea.

casa umbrella // exterior view // image courtesy of the architect

Also, it is a kind of criticism to the Buckminster Fuller dome. The Fuller dome is also a self-made dome, but from our experience, it isn’t so easy to make a Fuller dome by ourselves…. [laughing]. And so, mathematically and structurally it is a very futuristic plan, but Fuller’s proposal… for a disaster, it doesn’t work so well, because you should prepare it before the disaster! In the case of Casa Umbrella, there’s no need to make preparations.

Is that kind of idea about engaging with a social process present in a lot of your designs, or your installations?

Yes, yes… this umbrella is a little bit different from a standard one: it has an extra piece of material, you know?

The normal umbrella is shaped like this [gesturing], but this special umbrella has an extra triangular sheet, and people could understand that this means it is for disasters, and then the communication happens between the owners of the umbrella.

And also it can send a message: earthquakes can happen any time. If people see the umbrella they think, “Ah! The disaster can happen anytime!” That is a strong message to the people.

casa umbrella // interior view // image courtesy of the architect

So in a sense you’re trying to design a social interaction as well as a physical structure.

Yes, exactly!

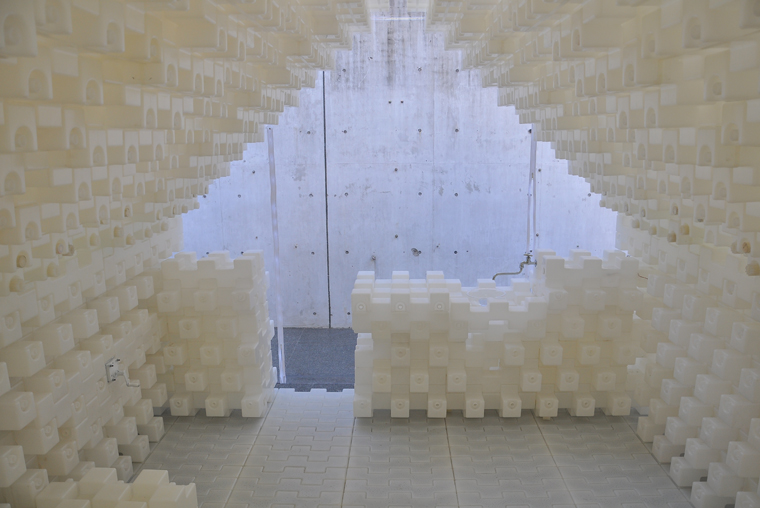

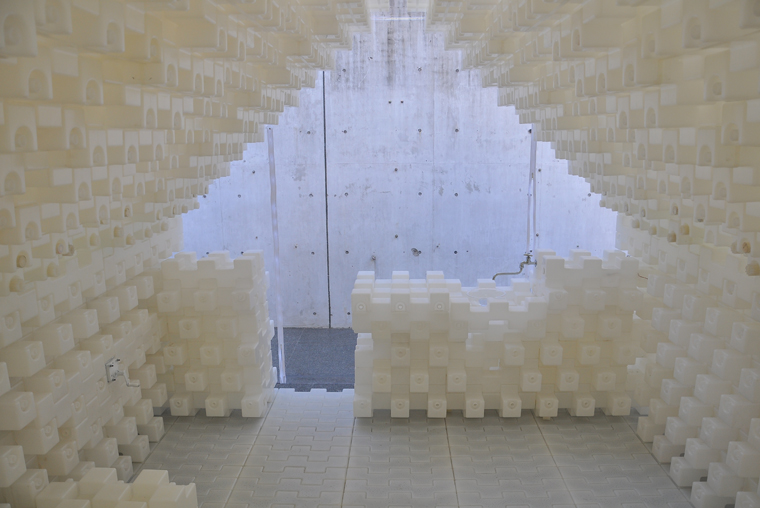

The second example I want to speak of is the Water Block House. The beginning of the idea is the poly tank, which is usually used for construction sites. It is this kind of big tank, it is light when it is empty; if it is filled with water it becomes heavy. I think it is a very good example of new flexibility: in the 20th century, flexibility was the positioning of the element. But the poly tank can change its essence, and this is very different. So I decided to use this material for building.

The first poly tank [we looked at] is just a poly tank, but the second version of the poly tank, the Water Block, has two caps. If we connect two caps together, water flows between them. And then it’s like a human body: a human body is cells and water flows, liquid flows. When this happens, we can control the temperature of the body, we can control the movement of the body; it is becoming very easy, with this kind of flow.

And so we designed the Water Block house for an exhibition at the Gallery MA, three years ago.

water block house // prototype interior view // gallery ma tokyo // image courtesy of the architect

It was at the MoMA in New York as well, right?

MoMA New York just showed the part, but in Gallery MA we completed a house, with the bathroom, kitchen, bed, lighting fixtures – people could actually live in that house. In that sense, the Water Block House is realizing the autonomy of the house.

Autonomy means not depending on the infrastructural system, because if we can have a solar heat gain unit, we can warm up the house, without gas, without electricity. And also that house has a solar generator. It’s like the human body: it’s very independent, we are not connected with the… the…

To the grid?

Yeah, to the grid. And that experimental house happened three years ago, but after the earthquake people understand how necessary this autonomy is. Because infrastructure is totally unreliable.

In the 20th century, people believed that the infrastructure, the government, is perfect, will never stop. But with such natural disasters, it is a very weak, fragile system. We finally know the weakness of that system.

water block house // module detail // moma new york // image courtesy of the architect

In both of the cases we've talked about, it seems like part of the interest for you is in new structural units.

Yes, and in the Water Block House the block itself is a structural system. I want to break the vertical separation of the disciplines: structures, air conditioning, piping systems… I want to bring it together. The human body is… all the systems are tightly, tightly combined. It is impossible to separate those systems! But in the architectural academy, the professors are separated and the studies are separated; and also construction sites, beginning from the structures, and the piping…all separated! I want to mix it, meld it.

You’re quite well known for innovative use of material, and it seems like that’s also present in your installations – are there things you have discovered from an installation that have been useful to you later on?

For us, those experimental projects are not [just] for experiments. The ideas from those projects can be adapted to bigger projects. For example, our chidori project - our chidori project started as a small toy. It’s a very unique joint, without any nails or any metal. We started from a small pavilion in Milan, but in seven years time we realized that idea for a real building [the Prostho Museum], and also that idea is going to a Starbucks project in Fukuoka.

Now the idea is going from the Starbucks to a new project for a Taiwan client. Using the same system, but much developed from Starbucks. And project by project, it goes to the next step.

prostho museum // interior view // image courtesy of the architect

Is that in your mind when you make these small things – is it in your mind that maybe the idea will become bigger next time?

Hmmm…. When I’m doing these, it’s just for that project. But after seeing that project, we get some new inspiration, and so then we can go on to the next step.

You seem to make quite a number of installations: is that because people offer them to you, or do you look for opportunities to make them?

People… basically people come with offers. And some I refuse and some I accept, because for business, those installations don’t make money at all! [laughing]

But! If we can achieve something in a small installation, we can go to the next step, and its very good for our office. Also the people, the energy of the office can be brought up by those installations.

Because they’re kind of exciting…

Exciting, and the result is very unexpected [laughing]: you think “Wow! Yeah, let’s go to the next step!” Architecture is too slow, but an installation…

You’ve returned to the tea house several times with your installations – is that a personal interest for you?

Yeah, the teahouse… I think that the teahouse, as a building type, was invented by Sen Rikyū in the 17th century – he utilized the teahouse to present his philosophy to the people.

And he was a very smart guy! Because the teahouse itself is very small, but the architectural design, with the activity inside… at first, he brought some flowers from the field into the teahouse – the selection of flowers means something. And then he brought some scroll from somebody else… the selection of those things is a great presentation to the people, and also the manner of serving tea itself is presentation.

floating teahouse // perspective view // image courtesy of the architect

Basically, his ethics came from the Zen religion, but for the people Zen religion itself is too far, too difficult to understand. But through those experiences in these small buildings, people can know, can understand the essence of the philosophy, the essence of the Zen religion.

And in that sense, he uses the teahouse as a form of communication, as a very wide-range communication between him and the people. And I would like to do the same thing. My small pavilion is a very good media to show our idea, to show our philosophy.

And so in that way it becomes part of a tradition, as a way to present a set of ideas.

Yes! And often we are serving tea in my pavilions. So for example, our Floating Teahouse, in Washington, D.C. in the National Building Museum, we did a tea ceremony. Also our Teehaus in Frankfurt is a pavilion for the tea ceremony; once a month, that museum is organizing a tea ceremony school.

And then, the experience of this tea and this space, they can work together to give an experience to the people.